- Home

- I. J. Singer

The Brothers Ashkenazi Page 2

The Brothers Ashkenazi Read online

Page 2

Of course, Isaac would never have even considered such self-serving prevarications had his brother lived. But a far more interesting counterfactual to consider (if such counterfactuals can be said to make sense) is whether Israel Joseph’s longevity would have blocked Isaac Bashevis’s finding his eventual way to his extraordinary talent. Satan in Goray transposes Singer’s moral dualism to the safe distance of the seventeenth century; The Family Moskat brings it very much home. He introduces, in the character of Asa Heshel, the first of the many stand-ins for Isaac Bashevis who will people his fiction, a would-be intellectual who languishes in half thoughts and daydreams, a libertine who never entirely sheds the invisible bindings of long-abandoned phylacteries. Isaac once told one of his earliest translators, Dorothy Strauss, that he thought that women caught in adultery should be hanged. Shocked, she asked him whether he really believed this, and he answered, “No, but I wish I did.” Behold Asa Heshel and countless other I. B. Singer protagonists.

Perhaps it was not just the intimidating stature of the older brother that kept the younger brother’s powers on hold but the thoroughgoing rationalism—“logic, cold logic,”—which the younger brother needed to resist in order to bring forth his art. One can feel the fierce intellect rising off the pages of I. J. Singer’s works, the passionate engagement with historical currents that would send him striding out of the shtetl, without any nostalgic glances backward, prepared to take on the world and assess it on his own terms. How much more overpowering must he have been in life, that older brother, and how difficult it must have been to take issue with him, to plead the other side, even within the private precincts of one’s own mind, where fiction can take fire only in the purity of perfect freedom to think and feel what one authentically thinks and feels. Hide from your own take on the world in there, and your fiction is doomed.

The acknowledgments page of The Family Moskat reads: “I dedicate these pages to the memory of my late brother I. J. Singer, author of The Brothers Ashkenazi. To me he was not only the older brother, but a spiritual father and master as well. I looked up to him always as to a model of high morality and literary honesty. Although a modern man, he had all the great qualities of our pious ancestors.” There is no reason to doubt this testament to profoundest love and reverence for the brother who had always facilitated his way. And yet—such are the dark mysteries of human nature, which I. B. Singer, of all writers, was prepared to acknowledge—it was only the death of the one brother that brought the genius of the other to life.

And so we return to the irony of introducing I. J. Singer by identifying him as the older brother of the late Nobel laureate, and most especially in the context of The Brothers Ashkenazi. The large-scale ambitions of this novel not only brought a new scope into Yiddish literature, its fluid plotlines carrying the heft of massive social and political forces, the collisions of its characters deftly tracing turbulent dynamics of history. But also—irony upon irony—fraternal rivalry is itself one of the novel’s major themes. It is the competitiveness between two brothers, twins separated not by nine years but five minutes, that fuels the outsize ambition. The implacable need that drives the central character, Simha Meir Ashkenazi, to leave his mark on the world is his habit of compulsively comparing himself to his brother, Jacob Bunem, the more physically prepossessing and charming of the two. Jacob Bunem’s acquisitions of love and riches seem to befall him passively, while Simha Meir must devote his every waking hour to achieving his dubious goal of becoming “king of Lodz,” a city whose unsavory devotion to the profit motive is the urban counterpart to Simha Meir himself, a textile manufacturer whose darting eyes are always looking for an opportunity for gain and who ceaselessly scrawls figures on any available surface—tablecloths, napkins—enraging his exquisite little wife, Dinele, who detests him.

The conquest of Dinele, who becomes Diana as her husband becomes Max, partly explains the rivalry of the brothers. Dinele had longed that the arranged marriage forced upon her by her wealthy Hasidic parents would yield her the romantic figure of Jacob Bunem as a husband rather than his obnoxious brother. Like many Polish girls, even from Hasidic households, Dinele had been sent to study at a secular Gymnasium, where she had been a great favorite of her Gentile friends, and she finds the ways of the Hasidic men, even her own father and brothers, boorish, degrading, and alarming. (I remember my own father telling me how this rift in the sensibilities of Jewish girls and boys, brought about by their very different educations, was creating societal difficulties in the Poland he’d grown up in, the worldly girls turning up their noses at the relatively uncouth yeshiva boys their fathers chose for them. Ironically, it was precisely because, as girls, their education mattered so little that the comparatively affluent among them were shunted off to Gymnasia, the smattering of kultur meant to make them more marriageable.) Because Simha Meir is known as a Talmudic prodigy, Dinele’s father is willing to pay a small fortune for the dowry, which is what allows Simha Meir to begin his seat-of-the-pants scramble to fulfill his ambitions. “All Lodz spoke of Simha Meir’s victory,” I. J. Singer writes, after a particularly stunning series of betrayals that removes many of Simha Meir’s obstacles to dominance. “ ‘Shrewd as they come … smart as salt in a wound. The guts of a pickpocket!’ people said. In Lodz this was the highest possible compliment.”

Both Lodz, the manufacturing and commercial center of Poland, and Simha Meir, its would-be king, present a face of capitalism so disfigured by cunning greed and ruthlessness that the reader has no trouble imagining the author as a young man running off to Russia to witness the glories of Bolshevism for himself. Even Simha Meir’s father-in-law, Haim Alter, a warm if weak man, an ardent Hasid who hires only Jewish workers in his factory, is, as owner, an unrepentant exploiter. He claps his soft hands to the Hasidic tunes his weavers sing as they work, but so underpays them that the candles he makes them pay for out-of-pocket as they work their intolerably long hours represent a major drain on their feeble resources. If anything, Haim Alter emerges as even more despicable than Simha Meir because of the smarmy pieties with which he coats his avarice. These are capitalists as an ardent Communist might render them, etching the portraits with vitriol.

And yet the vicious fallacies of class ideology that Israel Joshua learned so well for himself in the Soviet Union writhe on the page. Simha Meir is not only played off against his pleasure-seeking twin brother but against the almost sympathetic character (high praise in I. J. Singer’s fiction!) of Nissan, nicknamed in Lodz, “Nissan the Depraved.” The son of a fiercely uncompromising rabbi, with whom Simha Meir, too, had studied, Nissan rejects his father’s world with a vengeance.

Yes, he hated his father, and along with his father, he hated his holy books that spoke only of pain and were steeped in morals and melancholy; his Torah, so complex and convoluted that it defied all understanding; his whole Jewishness that oppressed the human soul and loaded it down with guilt and remorse. But most of all Nissan hated his father’s God, that cruel and vengeful being who demanded total obeisance, eternal service, mental and physical self-torture and privation, and the surrender of all choice and will.

Yet this seeming rejection proves to be merely a form of substitution, as Singer relentlessly hammers home. The father’s avenging righteousness, too pure for pity, has been transferred intact into the son, along with a life steeped in morals and melancholy, an ideology demanding total obeisance, eternal service, mental and physical self-torture and privation, and the surrender of all choice and will.

This business of choice and will is at the heart of this complex novel. A tyranny of determinism pushes the characters along, excising the possibility of autonomy, even—or most especially—at those moments when the characters seem to be most forcefully asserting themselves as free agents. This determinism issues both from innate character, announcing itself from the moment of birth—the twins emerge from the womb crying in voices that prophesize their contrasting personalities—and from the larger historical forces relentlessly a

t work. Simha Meir, in particular, drawing from inexhaustible reserves of ingenuity and drive, serves only to demonstrate, because of the very indefatigability of his exertions, the awful fatality and futility of human efforts in a world so thoroughly deformed by injustice, injustice that he himself is eager to turn to his advantage.

The very grandeur of Singer’s deterministic designs leaves his characters little room for self-reflection, narrowing their inner lives into dimensionless spaces. What defeats them is not their internal uncertainties and paralyzing dualities—as in so many of I. B. Singer’s portraits of human futility—but rather the inflexible joining of their innate characters with their historical circumstances. In one brief passage, a little masterpiece of the twisty tergiversations of self-deception, Nissan comes close to rethinking his politics. A demonstration planned for May Day has gone disastrously wrong. The workers, liquored and dangerous, quickly transition from humiliating a hated factory overseer to targeting specifically Jewish factory owners, and from there to beating up random Jews, who are fellow workers, their comrades by class. What was meant to be a demonstration of proletarian solidarity turns into a full-fledged pogrom, heads bashed, women violated, with the Polish authorities cynically waiting it out until the rage is spent. Nissan, stunned by grief and guilt at having aroused passions whose outcome he had not foreseen, briefly considers whether his presuppositions might be faulty:

Maybe man was essentially evil. Maybe it wasn’t the fault of economic circumstances, as he had been taught, but the deficiencies of human character.… He drifted off and suffered terrible nightmares replete with blood and carnage. Behind it all resounded his landlord’s words: “It shall be forever so …” Ungroomed, fully dressed, he lay on his cot for a day and a night as if in a stupor. He was roused by the morning sun shining as brightly as it could through the polluted Lodz air and dingy windowpanes. He no longer felt the despair that had consumed him, the apathy and loss of purpose. Instead, there surged within him a will to live, to restore himself, to forge something positive out of the tragedy and disappointment. Like his pious father, whose faith in the Messiah nullified all contemporary suffering, Nissan reaffirmed his faith in the validity of his ideals and pushed aside all negative thought.

Though I. B Singer, in his later attempts to distinguish himself from all previous Yiddish writers, often derided their sentimentality, his brother’s work is so starkly unsentimental as to run the risk of contracting a deadly aesthetic chill. A masterful rendering of the sweep of history, animated by indignation at its senseless cruelties, is all well and good; but a novelist must also swoop down into the living vulnerabilities of his characters and tear out our hearts. A novelist knows what utopians often forget—that human tragedies, no matter their scope, are suffered one life at a time, and their ultimate meaning is irreducibly singular. In the case of I. J. Singer, one imagines that the stench of sentimentality called forth much the same disgust as the stench of religion, making him loathe to pull too hard at readers’ heartstrings. Fortunately, he is artist enough to overcome the fatal fastidiousness, and, interestingly, it is often in scenes that involve his women characters that he closes the distance around the specific throb of the specific wound. The brutal wedding night of Dinele brings us so close to the living vulnerability of this girl as to be almost unbearable. So, too, does the death of a girl at the barricades and the effect it has on her father, Tevye, nicknamed by the workers “Tevye the World Is Not Lawless,” Nissan’s comrade in arms, the fiery revolutionary crumbling into a grief-stricken father.

If fatalism hangs heavily over all the action of The Brothers Ashkenazi, it hangs particularly heavily over the Jews. The promises of a purely secular world, one that would erase the difference between Jew and Gentile, no doubt seemed to I. J. Singer a lie so outrageous that it would be funny if it were not so painful. After the pogrom, the wives of the Jewish workers berate their battered husbands who had been inspired to strike by Nissan’s preachings: “Didn’t you know it always ends up with Jewish heads bleeding?” I. J. Singer’s adventures in the greater world led him to much the same opinion as the workers’ wives of Lodz. It is not religious backwardness or economic conditions or political theories that are ultimately to blame. These human constructs are only put to use for the evil that men would do. It is human nature itself that damns us, in I. J. Singer’s eyes. The possibility that Nissan can only glance at in his utter despair—the filth of corruption mixed into human nature—is the conclusion that Israel Joshua has arrived at.

Though he was convinced that it always ends with Jewish heads bleeding, I. J. Singer does not exclude Jews from his cynical reading of human nature. In one section of The Brothers Ashkenazi, he mercilessly portrays the Jews of Lodz succumbing to their own fine-hewed instincts for xenophobia, quickly assembling prejudices toward the Muscovite Jews who pour into their city after Czar Alexander III exiles them from their homes. These Moscow refugees are more sophisticated than the Polish Jews, and are dubbed Litvaks, meaning those who come from Lithuania, even though they are not from Lithuania. Apparently, in Lodz, Litvak is something of an insult. The two groups quickly get to work dredging up enough differences to support their mutual disapproval.

Traditional Lodz Jews were outraged. The elder Litvaks wore short gabardines, derbies, and fedoras. The younger were clean-shaven. They didn’t sway at prayer. They were more like gypsies than Jews. It was rumored that they could cast spells. When a Litvak moved into a house, all those who could afford to moved out. The Lodz men wouldn’t include a Litvak in a quorum. The Lodz women wouldn’t lend a pot to a Litvak neighbor lest she render it impure.

As Mark Twain famously said, “The Jews are human. That is the worst that can be said of them.” Israel Joshua Singer concurs.

Toward the end of The Family Moskat, Asa Heshel, accompanied by a Communist girlfriend with whom he is cheating on his long-suffering wife, Hadassah, visits the manically expansive friend, Abram Shapiro, who has served as something of a (failed) surrogate father to Asa Heshel, taking the young man under his wing as soon as he arrives in Warsaw, yet another rebelling former yeshiva prodigy eager to stretch his talents beyond the Talmud. And now it is the eve of World War II. The murderers are circling, and the Communist girlfriend has been offering some warmed-over propaganda, blaming everything on the capitalists. Abram, who has suffered a heart attack and is staring death straight on, has no more patience for nonsense, and stops her cold. “Just the same as the anti-Semites put the blame for everything on the Jew, that’s the way you Leftists put all the blame for everything on the capitalist. There’s always got to be a sacrificial goat.” “Then, according to your opinion, who’s to blame for the present crisis?” the girl asks, and I’ve always suspected that Abram’s answer echoes words that Isaac had heard spoken by his late older brother, an answer that is a more accurate, if encoded, testament to the fierce truthfulness of the man than the pious dedication at the front of the book. “Human nature,” Abram says. “You can call a man capitalist, Bolshevik, Jew, goy, Tartar, Turk, anything you want, but the real truth is that man is a stinker.”

Bad art, just like bad religion, sins against us by offering us false consolations. In this regard, let it be said that I. J. Singer’s art is sinless.

Introduction

IRVING HOWE

There are two Singers in Yiddish literature and while both are very good, they sing in different keys. The elder brother, Israel Joshua Singer (1893–1944), was one of the few genuine novelists to write in Yiddish. The younger brother, Isaac Bashevis Singer, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1978, has become a prominent figure in American literary life through the frequent translation of his work from Yiddish into English. The younger Singer is strongest as a writer of short stories and novellas blending folk and grotesque motifs, though he has also tried his hand, not very successfully, at the full-scale social or family novel.

Each of these talented brothers has won an American following, at different cultural moments and for s

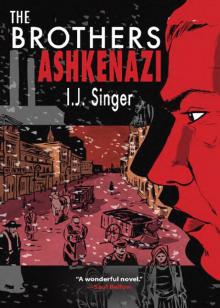

trikingly different reasons. When I. J. Singer was first published here in English translation during the thirties, his books—notably The Brothers Ashkenazi (1936)—gained a large popular success, appealing as they did to readers of traditional tastes, those who enjoy the sort of thick and leisurely family chronicle that dominated European literature at the turn of the century. For Yiddish writers, it should be stressed, this kind of novel did not come easily. The pioneer Yiddish “classicists” of the late nineteenth century—Mendele, Sholom Aleichem, Peretz—turned spontaneously to short fictions, as if seeking a modest form to go together with the narrow social range of the shtetl life that was their usual setting. Only with later Yiddish writers, those coming to prominence during the first few decades of this century, did the large-scale, many-layered “polyphonic” novel begin to flourish. And this, of course, was partly due to the increasing urbanization of the East European Jews, which, in turn, brought about a more complex latticing of classes than had been possible in the shtetl. It also brought about a new exposure to contemporary European culture, with its large variety of literary forms. The family chronicle or social novel in Yiddish, as The Brothers Ashkenazi vividly demonstrates, is both sign and cause of the increasing “Europeanization” of Jewish life in Poland and Russia.

The Brothers Ashkenazi

The Brothers Ashkenazi